In this essay, Professor Edwards, who has also visited the OUP archive, draws attention to the history of the Clarendon Edition that the archive reveals, noting that one of the most striking things about its contents "is the absence of any insight into (Vinaver's) most significant conclusion about the Winchester manuscript that led him to title his edition The Works of Malory, to see it as a series of narratives rather than the 'whole book' of Malory's own phrase" (p.81). What the archive does reveal, says Edwards, is a great deal about the personalities of the people who were part of the publication history of the Works. He describes the encounters with Walter Oakshott, and quotes from the letter posted here earlier in the month. He also shows the tension there was with Sir Frederic Kenyon, head of the British Museum and also head of the Fellows of Winchester College, who believed that Vinaver did not give Oakshott enough credit for his role in discovering the Winchester manuscript. Vinaver disagreed: "he simply stumbled upon the book and recognized, as any moderately educated Englishman would have done, that it was Malory's text", he said. "No one can dictate to me what I ought to say about the work done by Mr Oakshott" (OUP archive, 4 December 1945, quoted on p.80).

Kenyon was not impressed, and when the Edition came out in 1947 he wrote to the TLS (7 June) to draw attention to the debt he felt Vinaver owed Oakshott, accusing Vinaver of ignoring "the usual courtesies of scholarship." Vinaver appealed to Kenneth Sisam to step in on his behalf, but OUP refused to get involved further. This is not at all unreasonable if viewed in the context of the letters between Sisam and Kenyon and Sisam and Vinaver on this subject, where Sisam can be seen to be largely in support of Kenyon's objections: my own research has found that on 3 December 1945 Sisam wrote to Kenyon, saying: "Of course, I agree with you, and have put my thoughts very forcibly to Vinaver, telling him that the Preface must be cancelled and amended. I have not yet had his reply. He is an ableman, but inclined to be mulish."

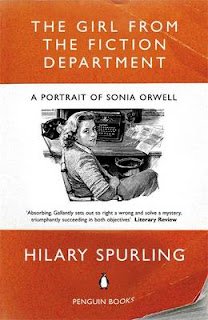

Perhaps the most sensational revelation that Professor Edwards makes regards the assistance Vinaver had in putting the Edition together. He reveals that the "permanent Assistant" Vinaver tells Sisam he has employed to help him with the work (OUP archive, 8 July 1938) was Sonia Brownwell, who famously went on to become the second Mrs George Orwell. Edwards has traced correspondence which shows it was likely that Brownwell was an infatuation of Vinaver's: a letter from Vinaver in 1938, quoted by Edwards from Hilary Spurling's biography of Sonia, The Girl from the Fiction Department (London, 2002), shows his eagerness to be with her: he counted on the sight of her to restore him as if by magic from the demands of work, and could "hardly wait" to catch the train to London, when he would "break all speed records" by taxi to get to her street door (p. 79). This does, perhaps, explain why he chose someone who, as Edwards notes drily, "was only nineteen and untrained in Middle English palaeography" (p. 79), to help him with such a vital task. Sonia's name is absent from the acknowledgements in the Preface to the Works, however, Edwards notes (p. 80).

This is not perhaps surprising: despite Spurling's description of Brownwell as looking

"as if she had stepped straight out of Malory’s romance" with "luxuriant pale gold hair, the colouring

of a pink and white tea-rose, and the kind of shapely, deep breasted, full

hipped figure that would have looked well in close-fitting Pre-Raphaelite green

velvet,” (Spurling, p. 25) the affair "if it was one, was short lived. Sonia had neither the inclination nor the temperament for the role of scholar's wife" (Spurling, p.28). Vinaver met his future wife, Elizabeth, the following year, so her disappearance would, under these circumstances, only seem to be natural.

Edwards's short essay is additional evidence, from the pieces of the archive that he focusses on, how valuable such a publishing archive can be in examining the history of editing Malory (or indeed of any other canonical writer). The people who helped Vinaver, who worked with him at the Press and behind the scenes to bring the Works to publication show the collaborative network that must exist for such an enterprise to be successfully completed. In posts to follow, I will look at more of the archive's stories (and there are a great deal more to explore!), expanding, in some instances on points Professor Edwards makes from his own observations, but also looking at episodes that haven't been examined before....I would argue that there is plenty of material of interest to scholars of Malory, however, including careful notes from Vinaver explaining how he is going to edit and present his new Edition, and perhaps more significantly, how the revised Editions had their own important histories, too.

No comments:

Post a Comment