Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur: The Once and Future Text

A research blog following the production progress of Boydell and Brewer's new scholarly edition of Malory's Le Morte Darthur, edited by Professor P.J.C. Field

Friday, 25 January 2013

Quick Update

Peter reports, with typical precision, that 95.5% of the checking of the Apparatus and Commentary, which will form Volume 2 of the new Edition, is now complete: he is aiming to finish this by the end of the month. He will then need to work through the sections of the text (Volume 1) sent out to his "Seven Heroic Helpers" (Peter's words) and address any comments and corrections they have made. But all is still roughly on schedule, so more news shortly!

Friday, 16 November 2012

New Essay on Editing Malory by Professor Tony Edwards

After a research trail that now has its own substantial archive, I have finally managed to see and read A. S. G. Edwards's essay "Editing Malory: Eugène Vinaver and the Clarendon Edition", in Leeds Studies in English, Vol XLI, 2010, pp.76-81. This volume, although listed as 2010, had been delayed in production, and so has in fact only very recently become available in hard copy (it is still not accessible online when I checked today).

In this essay, Professor Edwards, who has also visited the OUP archive, draws attention to the history of the Clarendon Edition that the archive reveals, noting that one of the most striking things about its contents "is the absence of any insight into (Vinaver's) most significant conclusion about the Winchester manuscript that led him to title his edition The Works of Malory, to see it as a series of narratives rather than the 'whole book' of Malory's own phrase" (p.81). What the archive does reveal, says Edwards, is a great deal about the personalities of the people who were part of the publication history of the Works. He describes the encounters with Walter Oakshott, and quotes from the letter posted here earlier in the month. He also shows the tension there was with Sir Frederic Kenyon, head of the British Museum and also head of the Fellows of Winchester College, who believed that Vinaver did not give Oakshott enough credit for his role in discovering the Winchester manuscript. Vinaver disagreed: "he simply stumbled upon the book and recognized, as any moderately educated Englishman would have done, that it was Malory's text", he said. "No one can dictate to me what I ought to say about the work done by Mr Oakshott" (OUP archive, 4 December 1945, quoted on p.80).

Kenyon was not impressed, and when the Edition came out in 1947 he wrote to the TLS (7 June) to draw attention to the debt he felt Vinaver owed Oakshott, accusing Vinaver of ignoring "the usual courtesies of scholarship." Vinaver appealed to Kenneth Sisam to step in on his behalf, but OUP refused to get involved further. This is not at all unreasonable if viewed in the context of the letters between Sisam and Kenyon and Sisam and Vinaver on this subject, where Sisam can be seen to be largely in support of Kenyon's objections: my own research has found that on 3 December 1945 Sisam wrote to Kenyon, saying: "Of course, I agree with you, and have put my thoughts very forcibly to Vinaver, telling him that the Preface must be cancelled and amended. I have not yet had his reply. He is an ableman, but inclined to be mulish."

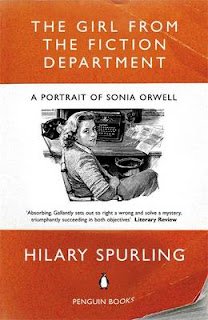

Perhaps the most sensational revelation that Professor Edwards makes regards the assistance Vinaver had in putting the Edition together. He reveals that the "permanent Assistant" Vinaver tells Sisam he has employed to help him with the work (OUP archive, 8 July 1938) was Sonia Brownwell, who famously went on to become the second Mrs George Orwell. Edwards has traced correspondence which shows it was likely that Brownwell was an infatuation of Vinaver's: a letter from Vinaver in 1938, quoted by Edwards from Hilary Spurling's biography of Sonia, The Girl from the Fiction Department (London, 2002), shows his eagerness to be with her: he counted on the sight of her to restore him as if by magic from the demands of work, and could "hardly wait" to catch the train to London, when he would "break all speed records" by taxi to get to her street door (p. 79). This does, perhaps, explain why he chose someone who, as Edwards notes drily, "was only nineteen and untrained in Middle English palaeography" (p. 79), to help him with such a vital task. Sonia's name is absent from the acknowledgements in the Preface to the Works, however, Edwards notes (p. 80).

This is not perhaps surprising: despite Spurling's description of Brownwell as looking

In this essay, Professor Edwards, who has also visited the OUP archive, draws attention to the history of the Clarendon Edition that the archive reveals, noting that one of the most striking things about its contents "is the absence of any insight into (Vinaver's) most significant conclusion about the Winchester manuscript that led him to title his edition The Works of Malory, to see it as a series of narratives rather than the 'whole book' of Malory's own phrase" (p.81). What the archive does reveal, says Edwards, is a great deal about the personalities of the people who were part of the publication history of the Works. He describes the encounters with Walter Oakshott, and quotes from the letter posted here earlier in the month. He also shows the tension there was with Sir Frederic Kenyon, head of the British Museum and also head of the Fellows of Winchester College, who believed that Vinaver did not give Oakshott enough credit for his role in discovering the Winchester manuscript. Vinaver disagreed: "he simply stumbled upon the book and recognized, as any moderately educated Englishman would have done, that it was Malory's text", he said. "No one can dictate to me what I ought to say about the work done by Mr Oakshott" (OUP archive, 4 December 1945, quoted on p.80).

Kenyon was not impressed, and when the Edition came out in 1947 he wrote to the TLS (7 June) to draw attention to the debt he felt Vinaver owed Oakshott, accusing Vinaver of ignoring "the usual courtesies of scholarship." Vinaver appealed to Kenneth Sisam to step in on his behalf, but OUP refused to get involved further. This is not at all unreasonable if viewed in the context of the letters between Sisam and Kenyon and Sisam and Vinaver on this subject, where Sisam can be seen to be largely in support of Kenyon's objections: my own research has found that on 3 December 1945 Sisam wrote to Kenyon, saying: "Of course, I agree with you, and have put my thoughts very forcibly to Vinaver, telling him that the Preface must be cancelled and amended. I have not yet had his reply. He is an ableman, but inclined to be mulish."

Perhaps the most sensational revelation that Professor Edwards makes regards the assistance Vinaver had in putting the Edition together. He reveals that the "permanent Assistant" Vinaver tells Sisam he has employed to help him with the work (OUP archive, 8 July 1938) was Sonia Brownwell, who famously went on to become the second Mrs George Orwell. Edwards has traced correspondence which shows it was likely that Brownwell was an infatuation of Vinaver's: a letter from Vinaver in 1938, quoted by Edwards from Hilary Spurling's biography of Sonia, The Girl from the Fiction Department (London, 2002), shows his eagerness to be with her: he counted on the sight of her to restore him as if by magic from the demands of work, and could "hardly wait" to catch the train to London, when he would "break all speed records" by taxi to get to her street door (p. 79). This does, perhaps, explain why he chose someone who, as Edwards notes drily, "was only nineteen and untrained in Middle English palaeography" (p. 79), to help him with such a vital task. Sonia's name is absent from the acknowledgements in the Preface to the Works, however, Edwards notes (p. 80).

This is not perhaps surprising: despite Spurling's description of Brownwell as looking

"as if she had stepped straight out of Malory’s romance" with "luxuriant pale gold hair, the colouring

of a pink and white tea-rose, and the kind of shapely, deep breasted, full

hipped figure that would have looked well in close-fitting Pre-Raphaelite green

velvet,” (Spurling, p. 25) the affair "if it was one, was short lived. Sonia had neither the inclination nor the temperament for the role of scholar's wife" (Spurling, p.28). Vinaver met his future wife, Elizabeth, the following year, so her disappearance would, under these circumstances, only seem to be natural.

Edwards's short essay is additional evidence, from the pieces of the archive that he focusses on, how valuable such a publishing archive can be in examining the history of editing Malory (or indeed of any other canonical writer). The people who helped Vinaver, who worked with him at the Press and behind the scenes to bring the Works to publication show the collaborative network that must exist for such an enterprise to be successfully completed. In posts to follow, I will look at more of the archive's stories (and there are a great deal more to explore!), expanding, in some instances on points Professor Edwards makes from his own observations, but also looking at episodes that haven't been examined before....I would argue that there is plenty of material of interest to scholars of Malory, however, including careful notes from Vinaver explaining how he is going to edit and present his new Edition, and perhaps more significantly, how the revised Editions had their own important histories, too.

Thursday, 1 November 2012

A "rather ludicrous situation" - Vinaver's letter to Sisam, June 1934

| ||||

| Vinaver's letter to Sisam |

PLEASE NOTE: THIS TRANSCRIPT AND THE IMAGE OF THE LETTER, ABOVE, ARE REPRODUCED BY KIND PERMISSION OF THE SECRETARY TO THE DELEGATES OF OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS.

as from The University Manchester

30.6.1934

Dear Sisam,

I have just returned from a most disappointing visit to

Winchester. My disappointment is due not

to the manuscript, but to the people in whose possession it happens to be, ie

the Fellows of Winchester, and I think I can say that what happened this

afternoon is unique in my long experience of libraries.

It seems hardly credible, but the fact is that they refused

to let me examine the manuscript except through the glass-case in which it is

exhibited. It was explained to me that a

few days ago someone (a man from Southampton whose name I do not know) applied

for permission to use the manuscript, and was asked to wait pending the

decision of the College as to what was to be done about it all. Having thus rebuffed one applicant, they

thought they were in honour bound to apply the same method to me. I had a long talk with a man called Oakeshott

– Keeper of the boys’ library. He is the

man who first discovered the MS and organised the exhibition of rare books in

the College. I found him most obliging

in many ways: he seemed genuinely upset about the rather ludicrous situation in

which I found myself, and chased round the cricket-grounds in the hope of

finding Kenyon who was watching the cricket-match. Instead, he found the Headmaster who told him

that the MS was not to be taken out of the glass-case. After that it was not much use looking for

Kenyon, as it was in any case not in Kenyon’s power to overrule the decision of

the Headmaster. ‘To brieve’ , as Malory says, all I could do was

to look at the MS through the glass and to examine the two pages which were

exhibited. This I did, and collated all

that I could see with Sommer’s text (which your Secretary kindly lent me last

night). It is obviously impossible to form any judgment on such a slender

basis. I enclose a few extracts from my

collation on a separate sheet.

The only thing that struck me as fairly certain was that

this manuscript could not have been copied from Caxton. Nor is it very likely (though on this point I

cannot speak with as much certainty) that Caxton used it.[1] There remains, therefore, only one

possibility which may [be] expressed as follows:

Malory

Winchester MS Caxton

The question is, of course, whether the MS gives a better

transcription than the Caxton. From the

two pages I have seen I cannot answer this question definitely, but I am

inclined to think that it is a more careful transcription: at least it supplies

some of the gaps in Caxton, and I do not think it will be possible to neglect

it in establishing the text. I am

strongly opposed to composite critical texts.

I think we ought to choose either Caxton or the MS and give in each case

important variants from the other. But

in order to decide which of the two texts deserves editing, I shall have to see

more of the MS. And here I come to the

practical issue. The meeting of the

College at which this matter is to be discussed, will be on July 14th. We must by then put definite proposals before

them. My suggestion would be that the MS

be sent to any place where it would be convenient for you to photograph[2]

some specimens of it (I want six pages at the beginning, six at the end, and a

fairly extensive piece from the middle portion – some 30 pages). This would probably give me sufficient

material to decide whether the text ought to be edited from the MS. If then we decide to stick to the MS, all the

remaining pages will have to be photographed (by this I mean, of course,

rotographed); and I think that in any case it would be most convenient if the

manuscript was deposited in the Rylands while the work of editing is going on.

I am to write to the Headmaster about it, but I should like

to know what you think of it all before I do anything in this matter. And in any case I think it would be advisable

if we both wrote to the same effect.

I am afraid this is rather a rigmarole. But I find it difficult to describe more

briefly my extraordinary adventure in Winchester.

I am looking forward to hearing your views.

Yours sincerely

E. Vinaver

P.S. As the Press is

closed till Monday, and I am leaving (for Manchester) to-morrow, I shall have

leave (sic) your Sommer in a parcel addressed to you at Lincoln. I am sorry I cannot bring it back to the

Press myself.

Sommer, pp.353-4.

P353. Sommer MS

l.12. Now

leve we here

sire la cote male tayle

l.16-17 her

conclusion was

that and hit pleasyd

syr

Tristram that he

wold come

l.21 he answerd

hym

that

l.25 blewe

hem on the

costes

l.26 castel peryllous

P..54

l.1-2 sawe afore hym

a lykeely Knyght

armed

sytthnge by a welle

and

a strange mighty

hors

passing nyghe hym

l.18 And thenne that

Knyght took a gretter

spere in his hand

and encountred

l.19-20 by grete force

l.26 cast

l.29 hold thyn hand

and telle me

|

Now leve we here of

Launcelot de lake

and of la cote male

tayle

her conclusion was

thus that if hit pleased

syr Trystram to come

he answerd hym and

seyde that

blewe them unto the

costs

foreyste perelus

(‘forest’ in the French)

Sawe before them a

likely Knyght sythynge

armed by a well and a

stronge mighty horse

stood passing hy Ȝ.

And anone that

Knyght took a grete

spear and encountred

by fortune and by grete

force

kest

hode thyne hond

a litylle whyle

and telle me

|

Spelling

Sommer

Thenne

Forest

Houses

Isoude

Tristram

|

MS

Than

Foreyste

Owrys

Isode

Tristrames, -us

|

On the shoulders of giants....

In the Preface to A History of Arthurian Scholarship (D.S. Brewer, 2006), Norris Lacy notes

that “with each passing year, the major contributions of the past appear more

remote, and we risk losing sight of previous trends and forgetting the

substantial achievements that, however outdated by current standards, permitted

or in many cases generated subsequent

scholarly efforts.” It is this debt that

this blog and this research seeks, at least in a very small part, to

acknowledge: looking at both the scholarly

and the publishing histories of key Arthurian texts and criticism, and

highlighting the part each side played in progressing the knowledge and

understanding of this literary and cultural legend.

Last week I visited the archives of Oxford University Press

and was granted access to files pertaining to Eugène Vinaver’s edition of

Malory. This cache of papers has yielded

more than I could have hoped for in terms of clear demonstration of the

involvement Vinaver’s editors at the Press had on his 3 volume Works, in all 3 editions. The papers reveal the energy, scholarly,

practical and diplomatic, employed to bring the Works to print, and the network

of connections running through the main scholarly editor – publishing editor

relationship. I hope to be able to write

up the findings in the coming months, and to post pieces on this blog.

Last week I visited the archives of Oxford University Press

and was granted access to files pertaining to Eugène Vinaver’s edition of

Malory. This cache of papers has yielded

more than I could have hoped for in terms of clear demonstration of the

involvement Vinaver’s editors at the Press had on his 3 volume Works, in all 3 editions. The papers reveal the energy, scholarly,

practical and diplomatic, employed to bring the Works to print, and the network

of connections running through the main scholarly editor – publishing editor

relationship. I hope to be able to write

up the findings in the coming months, and to post pieces on this blog.

All comments are welcome and encouraged: my own experience of Arthurian scholarship to

date has been a hugely positive one, with the International Arthurian Society

providing what has become a deeply appreciated academic ‘home’. The “giants” that Norris Lacy describes in

the Preface are, in Arthurian scholarship, part of its own compelling

story: and can be found in both academic

and publishing contexts.

So, to start with, my next post will be the transcription of

the letter Vinaver wrote to his editor of the time, Kenneth Sisam, after he had

visited Winchester to view the newly discovered Malory manuscript for the first

time. This letter expresses his disappointment

-- his extreme disappointment! – at only being allowed to view the manuscript

through the glass case it had been put in.

Sisam’s part in helping to smooth the way for the manuscript to be used

more fully will, I hope, follow in

future posts.

Wednesday, 3 October 2012

Arthurnet post from P J C Field

In answer to a post asking how the new edition will relate to the 1990 revised 3 volume edition, Peter wrote:

The short answer is implied in the last sentence of Boydell's blurb. Vinaver was, in textual critical terms, an extreme conservative (his views are regularly quoted in courses on editing as an eloquent exposition of that view), and I found, while revising his last 3-volume edition for the 1990 Clarendon Press Works of Sir Thomas Malory, that I disagreed strongly with him on that. He didn't always stick to his principles -- and thank goodness for that -- but he did sometimes, and among other things they required him to leave manifest error uncorrected if he couldn't not only prove that the reading of his base text was erroneous but also show how that error had come into being. And "prove" meant prove -- in principle, an editor needed certainty, not mere probability, before emending his base-text: in other words, he was obliged to leave unaltered in his text readings he believed were probably corrupt. I, however, thought an editor should (after making the best allowance he could for his own inclination to believe that a possible emendation was correct because it was awfully clever and he'd thought of it) go with whatever he believed was probable and see if the scholarly world agreed or thought he and his edition should be dropped together into the Bog of Eternal Stench. It was, however, impossible and would have been indecent for me to have tried to subvert Vinaver's principles in his own edition. There have also, since the last complete revision and resetting of the Works in 1967, been discoveries about the relationship between the two primary Malory texts (the manuscript was in Caxton's printing-shop, and got his ink on its pages), new discoveries about the sources Malory used, better editions of the sources that were already known, and invaluable research tools like concordances and the completed Middle English Dictionary. They weren't available to Vinaver, they were available to me. Hence my edition gives over 2000 readings different from those of the Works: it also has a different title (Le Morte Darthur) and a different layout, with a much cleaner page and no multi-page breaks between sections to remind you just how fragmented Vinaver thought Malory's book was. It will be in two volumes, the text in one and what you might call the long answer -- it's about as long as the text -- in the other. So if you want, you can just sit down with Malory alone in Vol. I without distraction, and if you want you can have both volumes open at the same time and read my stuff in parallel with the text it's designed to support.

A paperback student edition consisting of just the text plus the glossary from Vol. II is projected for some time in the future, but we need to get the main event achieved before we can even think about a date for that.

P. J. C. Field 26th September 2012

Arthurnet can be found at: http://www.arthuriana.org/arthurnet.htm

The short answer is implied in the last sentence of Boydell's blurb. Vinaver was, in textual critical terms, an extreme conservative (his views are regularly quoted in courses on editing as an eloquent exposition of that view), and I found, while revising his last 3-volume edition for the 1990 Clarendon Press Works of Sir Thomas Malory, that I disagreed strongly with him on that. He didn't always stick to his principles -- and thank goodness for that -- but he did sometimes, and among other things they required him to leave manifest error uncorrected if he couldn't not only prove that the reading of his base text was erroneous but also show how that error had come into being. And "prove" meant prove -- in principle, an editor needed certainty, not mere probability, before emending his base-text: in other words, he was obliged to leave unaltered in his text readings he believed were probably corrupt. I, however, thought an editor should (after making the best allowance he could for his own inclination to believe that a possible emendation was correct because it was awfully clever and he'd thought of it) go with whatever he believed was probable and see if the scholarly world agreed or thought he and his edition should be dropped together into the Bog of Eternal Stench. It was, however, impossible and would have been indecent for me to have tried to subvert Vinaver's principles in his own edition. There have also, since the last complete revision and resetting of the Works in 1967, been discoveries about the relationship between the two primary Malory texts (the manuscript was in Caxton's printing-shop, and got his ink on its pages), new discoveries about the sources Malory used, better editions of the sources that were already known, and invaluable research tools like concordances and the completed Middle English Dictionary. They weren't available to Vinaver, they were available to me. Hence my edition gives over 2000 readings different from those of the Works: it also has a different title (Le Morte Darthur) and a different layout, with a much cleaner page and no multi-page breaks between sections to remind you just how fragmented Vinaver thought Malory's book was. It will be in two volumes, the text in one and what you might call the long answer -- it's about as long as the text -- in the other. So if you want, you can just sit down with Malory alone in Vol. I without distraction, and if you want you can have both volumes open at the same time and read my stuff in parallel with the text it's designed to support.

A paperback student edition consisting of just the text plus the glossary from Vol. II is projected for some time in the future, but we need to get the main event achieved before we can even think about a date for that.

P. J. C. Field 26th September 2012

Arthurnet can be found at: http://www.arthuriana.org/arthurnet.htm

Wednesday, 12 September 2012

"Malory completed his Morte Darthur in 1469-70. The two earliest

surviving witnesses, the Winchester manuscript and Caxton's printed

edition, were both produced within the next sixteen years. The

manuscript was soon lost, but its rediscovery in 1934 revealed that

these two texts had striking differences. Eighty years of scholarship in

a variety of disciplines has discovered a good deal about who changed

what and why: the Caxton, for instance, tends to be very unreliable in

the last few lines of particular kinds of pages. These discoveries

should make it possible to produce an edition of Malory's book that

comes closer than ever before to what Malory intended to write. The

present edition aims to do that, basing itself on the Winchester

manuscript, but treating it merely as the most important piece of

evidence for what Malory intended, and the default text where no other

reading can be shown to be more probable."

This is the blurb on the Boydell and Brewer website for the forthcoming Edition, edited by P J C Field, of Malory's Le Morte Darthur. The current due date is listed as November 2013, and anticipation for its arrival has been growing among Arthurian scholars: Peter Field's work on Malory is internationally recognised, and his Edition will be a strong contender to replace Eugene Vinaver's 3 volume OUP edition (1947, and then revised by him in 1967 and then by Field in 1990) as the standard scholarly version of the fifteenth-century literary classic.

As a researcher working on publishing practices as well as medieval and particularly Arthurian texts, I wanted to look at the ways the scholarly and publishing imperatives act on such a canonical edition: shaping its overall physical and bibliographical presence, as well as its scope, readership and use. This research project focusses on the new Malory, hoping to capture the publishing history of this Edition, including those paratextual elements that are often so easily lost, but so valued by researchers. I've been granted access to the conversations between Peter Field and Richard Barber, who is the Editor at Boydell responsible for bringing the book through the publication process. Richard is, of course, himself an internationally recognised expert on medieval and Arthurian topics, so the editorial communications on the text are particularly well informed from both sides. I will be investigating the publishing histories of other editions of Malory, visiting archives and reporting on findings, and interviewing and recording reactions and responses from readers and scholars who are involved with the new Edition, looking at the influences such texts can have, and trying to map some of the consumption paths generated by marketing materials, scholarly networks, and less formal communication circuits, as the production and publication progress develops.

This is the blurb on the Boydell and Brewer website for the forthcoming Edition, edited by P J C Field, of Malory's Le Morte Darthur. The current due date is listed as November 2013, and anticipation for its arrival has been growing among Arthurian scholars: Peter Field's work on Malory is internationally recognised, and his Edition will be a strong contender to replace Eugene Vinaver's 3 volume OUP edition (1947, and then revised by him in 1967 and then by Field in 1990) as the standard scholarly version of the fifteenth-century literary classic.

|

| Peter Field |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)